The Garden: Volume Six

Uniquely Connected & Thriving Together at Dietrich College

In This Issue: A Message from Richard Scheines | Granovetter Challenges M.D.-P.h.D Inequities | Gardeners at CMU: Nisha Shanmugaraj | Ensuring a Diverse, Equitable, and Inclusive Faculty with Jeria Quesenberry | Reflection with Clara Lam: Panel On Anti-Asian Racism and Solidarities of Resistance | Op-Ed by Jayla Hemphill: To matter: to have significance and importance; to be worthy. | Grow A Garden - A Dietrich Student-Led Exhibition | Charting Our Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Path Forward.A Message from Richard Scheines

Bess Family Dean

Dietrich College of Humanities and Social Sciences

Dear Community Members,

I hope that your winter break has been restful, your health has been good, and your spirit rejuvenated!

This past fall, we hosted a forum: "Charting Our Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Path Forward," which highlighted the many contributions from staff, students, and faculty – transforming our conversations into action. These leaders are helping us create a culture that promotes and sincerely embraces diversity, equity, and inclusion while fostering belonging. I am grateful for this work, and for all of you who contribute to improving Dietrich in any way, large or small. Some highlights from the forum:

- Launching new professional development;

- Increasing yield with our student admissions;

- Investing in access and support through initiatives such as LEAP and Tartan Scholars;

- Providing meaningful community engagement through the Pittsburgh Summer Internship Program;

- Faculty search and hiring practices to expand our pool of candidates that have already succeeded in changing the makeup of our most recent two or three cohorts.

Much progress, but much work to be done — The work never stops. Let's all use every bit of strength, determination, intellect, positivity, and passion we have to move forward with grace, civility, and compassion; but let's continue to move forward. I hope we can actually gather in person later in the spring, and I look forward to all we will accomplish as a community of Gardeners!

Best,

Dean Scheines

Granovetter Challenges M.D.-P.h.D Inequities

Academic medicine, like many fields, faces structural inequities and disparities in gender, race, and class representation. Addressing this problem starts at not only encouraging individuals in underrepresented groups in medicine (URiM) to apply to postgraduate training programs, but also improving the overall accessibility of said programs.

Academic medicine, like many fields, faces structural inequities and disparities in gender, race, and class representation. Addressing this problem starts at not only encouraging individuals in underrepresented groups in medicine (URiM) to apply to postgraduate training programs, but also improving the overall accessibility of said programs.

Michael Granovetter (he/him), a sixth-year trainee in Carnegie Mellon University and the University of Pittsburgh’s joint M.D.-P.h.D Medical Science Training Program, found that the COVID-19 pandemic underscored the already existing disparities in academic medicine and medical training more broadly. But he saw that the virtual environment that grew prominent during the pandemic could be a critical tool for outreach.

“There are programs that charge medical school applicants hundreds of dollars for admissions coaching,” Granovetter said. “In a field that already favors applicants from higher socioeconomic and advantaged backgrounds, I felt that there are ways we could give advice to applicants, free and virtually.”

Granovetter and an M.D.-P.h.D. student at Columbia University, Eunice Lee, connected and decided to host a panel to help undergraduate students learn how to apply to physician scientist training programs and how to deal with the additional challenges of applying during a pandemic.

The American Physician Science Association (APSA) approached both Granovetter and Lee offering resources and tools to make their idea a reality. Following a successful pilot panel that was attended by hundreds of physician-scientist trainee program applicants, they fully realized the power of Zoom as a tool of accessibility.

“There was a gigantic need for a resource like this,” he said of the first virtual panel. “A lot of folks reached out to us and said the information was quite new to them. We were thinking about how many students come from institutions that don’t have pre-medical offices who wouldn’t have access to this information. And how many first-generation college students, or first generation medical or Ph.D. students could significantly benefit from the insights of current trainees, faculty, and program directors.”

At APSA, Granovetter now serves on the Justice, Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion (JEDI) committee, as well as co-chairing for the Virtual Content Committee. In his role, he and Lee launched the APSA Applicant Interactive Series, a series of online panels aimed to address each part of the M.D.-Ph.D. and D.O.-Ph.D. application processes, as well as introduce undergraduates to physician scientist training in the first place.

“M.D.-Ph.D. programs in particular have a disproportionately small percentage of students from underrepresented groups in medicine being admitted to these programs, in part because of barriers such as lack of knowledge, resources, information, and contacts,” he said.

The APSA Applicant Interactive Series is free and open to all. It is focused on supporting smaller institutions without pre-medical offices, community colleges, and Historically Black Colleges and Universities. Granovetter and his team have worked to advertise the series with organizations advocating for students from groups underrepresented in STEM.

Granovetter continues to do work in the space of JEDI for not only APSA, but within his medical school.

“I’m invested in transforming aspects of medical and graduate education,” he shared. “In my training program, I’ve been involved in a range of initiatives surrounding issues ranging from mentorship to student wellbeing to expansion of social justice elements in our curriculum.”

Gardeners at CMU: Nisha Shanmugaraj

Nisha Shanmugaraj (she/her/hers), a fourth-year Ph.D. candidate in the English Department’s Rhetoric program, aims to analyze how Indian (South Asian) American women cope with and disrupt the model minority stereotype.

Nisha Shanmugaraj (she/her/hers), a fourth-year Ph.D. candidate in the English Department’s Rhetoric program, aims to analyze how Indian (South Asian) American women cope with and disrupt the model minority stereotype.

“The stereotype suggests that Asian Americans are a success story of the American dream. They are a ‘model’ that other minorities should follow,” Shanmugaraj explained. “Because the model minority stereotype is positive, the ways it is socially violent are often overlooked, both to affected individuals themselves and to any potential minority solidarity that may exist.”

As an Indian American woman herself, this dissertation is personal to Shanmugaraj. Her research thus far has involved qualitative interviews with 25 women, and using rhetorical analysis to see how the model minority myth is experienced and resisted. Data from those interviews have brought up distinctions in responses based on racial identity, inflections of gender, parent relationships, interactions with white colleagues or peers, and more.

“Understanding that rhetoric is not just reading presidential speeches, but also more broadly how meaning is made and communicated, and how it occurs in nonverbal interactions, is important I think,” Shanmugaraj said. “I don’t have to look at texts. Rhetoric can be meanings made through a look or feeling, that are made time and time again. Rhetoric can expose the invisible processes that occur in the world that shape our identities and who we are in good ways and bad ways.”

An example of these repetitive processes is asking the question, “Where are you from?” particularly to minorities. The question, she explained, conditions the person being asked to believe that they do not belong here, or are conditionally here. Fortunately, a trend found in the interviews is that Indian American women are beginning to unlearn or disidentify with the stereotype.

“A moment of disidentification, which is a concept from José Esteban Muñoz, is when someone identifies or agrees with a norm like the model minority myth, and then actively breaks from that dominant narrative,” Shanmugaraj said.

She finds that now, more than ever, disidentifying with norms including the model minority myth is crucial. Movements such as South Asians for Black Lives demonstrate that Asian Americans––second and third generation Asians in particular––are eager to build solidarity and engage in political activism in a way that is intersectional.

It is this transformative aspect of her research that Shanmugaraj is eager to apply in the first-year writing courses she teaches. Just as her research has revealed the ways Indian-American women have criticized narratives that have been enforced all their lives, the classroom can be where students learn to disrupt and critique how our society functions.

“By applying my research in the classroom, I hope to further an anti-racist pedagogy and help underrepresented minorities critique their own feelings of nonbelonging,” Shanmugaraj said.

For a time, Shanmugaraj had to face her own feelings of non-belonging when it came to pursuing her doctorate. She credits faculty in the Department of English for giving her the push she needed to apply and pursue rhetoric research.

“I did not think I was ‘Ph.D. material’ for a very long time. Doctoral work felt very sophisticated, elevated, and scholarly in a way that I didn’t necessarily feel about myself,” said Shanmugaraj. “My advisor Dr. Stephanie Larson and mentor Dr. Joanna Wolfe definitely made the space of academia accessible, showing that it has practical application, and that I can do this.”

Though the process of writing a dissertation is long and arduous, Shanmugaraj is eager for the impact of her completed research.

“I think a lot of [South Asian and Indian Americans] grew up in white-predominant areas, so it feels isolating. There is not a lot written about this experience,” Shanmugaraj shared. “I hope to turn my research into something that other young Indian American women can read and feel less isolated. If it even just reaches one person that is enough for me.”

Ensuring a Diverse, Equitable, and Inclusive Faculty with Jeria Quesenberry

Over the past few years, Dietrich College has taken strides in following the mission of diversity, equity, and inclusion. Our Strategic Plan 2025 describes recommendations and programming meant to recruit and maintain a diverse, equitable, and inclusive community––and on the faculty side of this mission is Jeria Quesenberry (she/her/hers), associate dean of faculty within Dietrich College.

Over the past few years, Dietrich College has taken strides in following the mission of diversity, equity, and inclusion. Our Strategic Plan 2025 describes recommendations and programming meant to recruit and maintain a diverse, equitable, and inclusive community––and on the faculty side of this mission is Jeria Quesenberry (she/her/hers), associate dean of faculty within Dietrich College.

Quesenberry, who is also a teaching professor in the Information Systems program, has been in this role for about a year and a half. As associate dean of faculty, she is responsible in numerous areas concerning Dietrich College faculty, such as assisting faculty with reappointment, promotion, and tenure processes, as well as faculty hiring and onboarding.

In the space of diversity, equity and inclusion, the process of hiring and onboarding has been of utmost importance. Within Dietrich College’s Strategic Plan for Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion, hiring has a two-pronged goal: focusing on bringing in the world’s best faculty and being inclusive in the process. Through the leadership of Quesenberry, as well as Dean Richard Scheines; Associate Dean for Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Ayana Ledford; and James M. Walton University Professor of Economics Linda Babcock, developing best practices for hiring was a priority this year.

“We pulled together a guide of different best practices that departments used in their own hiring processes,” Quesenberry shared. “We piloted them this past year, and this year we are using them more broadly. We recognize that there is always room for improvement in hiring practices.”

The piloted best hiring practices were used in searches in our Psychology, History, and Modern Languages departments. All three departments, Quesenberry said, had success in their search processes. This is just the beginning for improving faculty recruitment, and Quesenberry has many aspirations.

“We’ve done pilots and debriefs, but for this year, given that we have another round of searches underway, we will have two years of experience to draw upon. We can really ask ourselves if the practices are as effective and promising as we believe them to be,” she explained. “One of my goals is to continue to monitor the pulse on hiring processes, and see what is working and where there are persistent gaps that Dietrich College can improve on.”

Another major goal of Quesenberry’s is to ensure that faculty recruitment is broad in nature, in the hopes of making hiring more inclusive. Increasing transparency in hiring practices is also imperative to inclusivity, but also to fairness and openness, especially in the evaluation of potential candidates.

“It’s important to recognize that hiring is not intended to be checking off a box or getting a ‘diversity hire,’” Quesenberry said. “It’s about putting forward a consistent, fair, transparent process to help combat bias.”

Simply hiring faculty with the tenets of scholarly excellence and inclusivity, Quesenberry and Dietrich College leadership recognize, is not an end-all solution. Quesenberry hopes to continue focusing on how the onboarding process for new faculty works, and if there are programmatic approaches that can be implemented for them, especially programs in community building, work climate, and work culture.

“Hiring is just one step in this,” Quesenberry said. “Bringing in new faculty into a scenario where we are not meeting their needs and helping them succeed means that these efforts are for naught.”

Unsurprisingly, Quesenberry’s research background in the technology workforce has greatly influenced how she approaches her role as associate dean for faculty. Her research focuses on understanding the factors that impede women's success in entering, obtaining, or persisting in technology careers. While academia is not the same as the technology workplace. Quesenberry has found that some of the barriers women in tech face are consistent with barriers underrepresented faculty may experience in the academic workplace: social expectations, work climate, and more.

“In this role, I am really excited to take what I’ve done from a research perspective, look at what our departments and university are doing, and take action to make a difference,” she shared. “It’s really rewarding to take that knowledge and use it in this way.”

For any questions or concerns about faculty hiring and onboarding, Jeria Quesenberry can be reached at jeriaq@andrew.ozone-1.com.

Dietrich College’s Guidance for Faculty Searches and Hiring

Note that a Carnegie Mellon University login is required.

Reflection with Clara Lam: Panel On Anti-Asian Racism and Solidarities of Resistance

On Sept. 30, Dietrich College co-sponsored a virtual panel about the rise of anti-Asian racism and solidarity building as resistance. The idea came to the minds of Dietrich College Associate Dean for Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Ayana Ledford, and Head of the History Department Nico Slate last spring. To bring this event to life, they approached and worked closely with the current advocacy chair for Carnegie Mellon’s Asian Student Association, Clara Lam (she/her/hers).

On Sept. 30, Dietrich College co-sponsored a virtual panel about the rise of anti-Asian racism and solidarity building as resistance. The idea came to the minds of Dietrich College Associate Dean for Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Ayana Ledford, and Head of the History Department Nico Slate last spring. To bring this event to life, they approached and worked closely with the current advocacy chair for Carnegie Mellon’s Asian Student Association, Clara Lam (she/her/hers).

Lam is a second-year student studying information systems with a minor in business analytics. As advocacy chair, she focuses on uplifting Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) issues and causes within ASA.

“I thought it was a great idea to have this panel on the topics of anti-Asian racism and solidarities,” Lam said. “People are realizing more that there is racism toward Asians. In the past, anti-Asian racism was almost hidden.”

With the help of Dietrich College, Lam created questions for the three panelists, structured the event, and was able to moderate. She was aware of the varying levels of knowledge audience members may have had coming into the virtual conversation, and kept that in mind while planning.

“How would you define the term Asian American? What were the panelists’ thoughts on model minority myth? These types of questions let each of the panelists respond with their respective perspective,” she said.

The perspectives of the numerous academics were also beneficial in demonstrating that anti-Asian racism is multifaceted and has a long, painful presence in the United States.

“Professor Judy Wu talked about the history of anti-Asian racism and how it has transformed throughout history, while Professor Van Tran offered a sociology perspective. The conversation also looked at the individual psychological effects of racism,” Lam explained.

An overarching message from the three panelists was that the U.S. history curriculum is lacking in properly representing Asian American stories. Universities as institutions, they shared, could offer more courses about the lived experiences of Asian Americans.

“I’m Asian American but I didn’t know much of Asian American history beyond the Chinese Exclusion Act, or the internment of Japanese Americans until recently,” Lam agreed.

One of the events Lam had learned about was the 1900-1904 bubonic plague in San Francisco. After having associated the plague with the city’s booming Chinatown, non-Asians reacted by effectively quarantining the entire town––even though most infected persons were of European descent.

“Another topic that was brought up was how solidarities of resistance in Asian American communities strengthened over time and different generations,” Lam shared. “The panelists emphasized that demonstrating solidarity can look like coming to events like this, educating yourself on the history, talking to people, and reaching out for emotional support when you need it.”

Despite the Zoom format, well over 50 attendees were present, which surprised Lam in the face of a community eager to resume in-person events. She believes this is tied to the fact that people now more than ever want to talk about issues related to anti-Asian racism and the Asian American experience. An audience member shared that they were really glad to see this event as a part of everyday life, not in reaction to something tragic happening, Lam shared. Overall, the panel on Anti-Asian Racism and Solidarities of Resistance was a success and has inspired the idea of future collaborations between student organizations and Dietrich College.

“If the opportunity comes, I would love to collaborate with Dietrich again. As advocacy chair, my term does end soon but I want to do more in-person small events where people can talk about their experiences and learn more about AAPI issues.”

Op-Ed by Jayla Hemphill: To matter: to have significance and importance; to be worthy.

How does one go about developing the belief that they matter, in any capacity? One develops the belief that they matter as we assure them that they are worthy of something, even if that may be the minimal standard of being alive. One might know that they matter because they have felt the feeling of mattering, knowing that their trauma and their future matters, knowing that their suffering is echoed and met with solvency. Their education is a worthy cause and their mental wellbeing a noble one. They might feel that they matter in the comfort of knowing that should they ever be endangered, that American law enforcement would first be called without fear of escalation, and second, that they would arrive in a timely manner. If one should understand the feeling of “matter” as one to be cultivated through social and societal investment, would they not also have to admit that the feeling of matter is nonexistent in the Black community?

How does one go about developing the belief that they matter, in any capacity? One develops the belief that they matter as we assure them that they are worthy of something, even if that may be the minimal standard of being alive. One might know that they matter because they have felt the feeling of mattering, knowing that their trauma and their future matters, knowing that their suffering is echoed and met with solvency. Their education is a worthy cause and their mental wellbeing a noble one. They might feel that they matter in the comfort of knowing that should they ever be endangered, that American law enforcement would first be called without fear of escalation, and second, that they would arrive in a timely manner. If one should understand the feeling of “matter” as one to be cultivated through social and societal investment, would they not also have to admit that the feeling of matter is nonexistent in the Black community?

Should one ever feel worthy while having to convince greater society that they are? Should one consistently feel that they matter as they are nudged to the margins until another of their kin is shot down needlessly in the streets of Minneapolis? Then, only when they scream and cry and make a fuss, disturbing others, will they be rushed to the stage to reaffirm that, yes, people like them still matter. One’s “matter” is diminished the moment that they must defend it, and becomes counterfeit as they are met with aggressive accusations of their death having been their own fault. They took or sold drugs, or maybe they were not the kindest person, they were aggressive or conducted themselves incorrectly, and so they deserved death. Being morally flawed is punishable by death, and if that death was served to them by an officer that paraded as an executioner that day, then it is just.

The feeling of matter appears to be circumstantial. Whatever mess of a society we have made has swallowed the feeling of “matter” whole. When we as individuals matter, we must matter unconditionally or not at all. Black lives can not matter, not when there is a discourse about the truth of it. There is no “matter” here, but a sadistic society that sees an ounce of acknowledgement as just for a daughter that now has all seven shots committed to memory. Her father, Philando Castile, must not matter, not if we count his value in bullets, and the possibility that she matters is simply out of the question.

Let us not be mistaken in thinking that the rare justice received is a testament to the feeling of mattering. If there were “matter” in the first place, black people would not be dying at the hands of law enforcement. Their families would not be confronted with the death of a loved one, and much less the knowledge of them being killed needlessly. That is not what mattering feels like, and is far removed from the “matter” that we march for. Mattering does not feel like grief, and must not be asking “Am I next?”

To matter must be cultivated in valuing black contributions, education, mental health, trauma, and black futures. If black lives only matter once they are lost, then how could one say that they matter at all? Surely, Floyd did not feel that he mattered as he called for his mother, remembering that in the moments before death, he called for that feeling of mattering, and society only answered once he was gone.

It must be noted, however, that this is the very same society that diminishes the degree of black lives mattering as they exist — the same society that hesitates to fund black prosperity. Black trauma is outdated. Black parenthood is “broken,” and so it must be invalid. Black futures were never truly secure, a black man loses nothing when choked to death in broad daylight, as society never did attribute “matter” to his living or future. The degradation of black existence is an ongoing cycle, the opposite of mattering, and the only thing that society has to show for itself in the way of affirming that black lives matter is not social or societal investment, but brief eras of acknowledging the regular tragedy of black suffering.

Black humanity and personhood are treated as concepts that matter only on occasion. Black contributions — black music, black dance, black food, black dress, black culture, they matter consistently. There is no modern society without black contributions, but black contributions do not feel, black people do. Black individuals have poured their souls into the foundations of society as we know it, yet we remain quick to dismiss their troubles and deprive our black communities of what it feels like to matter.

To matter must be some characterization of bliss where one does not fear the consequences of not mattering, if that fear should be the apprehension of being pulled over. If that feeling of fear and helplessness could extend beyond blackness, we would have to admit that black people do not matter to society, because that is not what mattering feels like.

A just society would not be so cruel to force its constituents to lay their dignity on the streets of every major city within its borders and demand justice. A society that cultivated the feeling of mattering would not require the sprawling of the words “Black Lives Matter” on its avenues. Where black lives matter solely on occasion, naming streets “Black Lives Matter” serves only to pacify the rage until the next victim is taken on the neighboring roads. If “matter” were present, it would be salient and entirely undeniable, a constant state of being that remains through the rain, one that cannot be painted over after the cries fade.

Grow A Garden - A Dietrich Student-Led Exhibition

Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, BXA senior Eileen Lee (she/her/hers), who studies art and psychology, began to regularly garden more with her parents. Gardening became Lee’s escape from working on her laptop all day, and as a great way for her to get some exercise and sunlight.

Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, BXA senior Eileen Lee (she/her/hers), who studies art and psychology, began to regularly garden more with her parents. Gardening became Lee’s escape from working on her laptop all day, and as a great way for her to get some exercise and sunlight.

“I found that being outside with nature—all the plants, bugs, and soil—really helped improve my wellbeing and mental health,” shared Lee. “I started to appreciate plants a lot more, and I thought of the idea of a plant party, where friends can gather to celebrate plants, well-being, and art.”

This “plant party” became “Grow A Garden,” a collaborative, student-led art exhibition that took place in November at The Frame gallery. In partnership with the Mindfulness Room, “Grow A Garden” featured 10 artists, including Lee. One of the artists featured is Adhiti Chundur (she/her/hers), a senior in human-computer interaction and cognitive psychology.

“I do art just for fun, it’s not related to my major at all,” Chundur said. “But exhibitions like ‘Grow A Garden’ let me intentionally create art with other students, and with a real deadline.”

The various installations and art pieces in “Grow A Garden” had a common thread: examining human’s relationship with nature, specifically plants, bugs and the like. From watercolor paintings to a vine-cladden virtual reality headset, the featured artists explored plants and nature, and how they help people slow down from their stressful day-to-day lives.

Chundur contributed to “Grow A Garden” with three pieces: two watercolor paintings, Lush and Reflection, and a digital projection called Metamorphosis.

Chundur contributed to “Grow A Garden” with three pieces: two watercolor paintings, Lush and Reflection, and a digital projection called Metamorphosis.

“I love being in nature as a way to reset and destress, especially after a hard week. I used to go to national parks with my family and always try to go to a park after a stressful day,” Chundur explained. “Lush is about that. The leaves and plants that are spreading in and around this woman’s eyes and mouth represent the internal reset I have when being in nature.”

In a similar fashion, Reflection is about how being surrounded by nature literally allows a person to pause and reflect. The choice to color the foliage blue, Chundur shared, was to emphasize the peacefulness of nature.

Metamorphosis is an interactive digital projection piece that allows viewers to reimagine what the human relationship with nature and sustainability could be in the future. Chundur created it originally for a class during the Spring 2021 semester—fortunately, Lee remembered Metamorphosis when initially planning “Grow A Garden” and reached out for more art from Chundur.

“Eileen was the person who thought of the idea and did all of the proposals with other art students,” she said. “‘Grow A Garden’ is her brain child.”

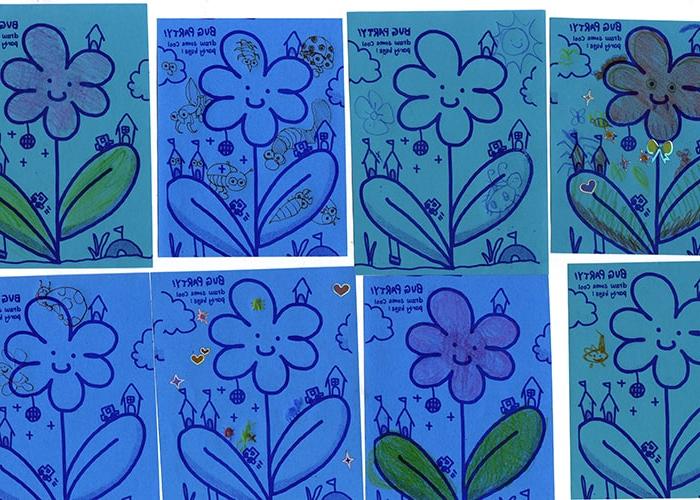

Besides leading most of the student collaborative efforts and reaching out for faculty input, Lee had her own art displayed. On clothesline, Lee displayed riso and linocut prints of plants and bugs; additionally, similar to Metamorphosis, one of Lee’s contributions—“bug party” cards and coloring pages—were interactive, allowing visitors to color, draw and reflect on their relationships with nature.

“I wanted our many visitors to take home a print of their own to put up in their homes,” Lee said. “The ‘bug party’ prints not only encourage people to color in and draw fun bugs, but remind them of nature and our exhibition when taking the prints home.”

There were many steps in organizing an entire exhibition, from finding sufficient funding to gathering necessary supplies. Fortunately, Lee did not endure this process completely alone: she leaned on many for advice, including the nine other artists, her advisor Dr. Crista Crittenden, the director of the Mindfulness Room Angela Lusk, and staff at the Frame.

“Overall, organizing and curating an exhibition to this scale on my own was super rewarding,” Lee shared. “As I’m graduating, I definitely look forward to creating more delightful and playful experiences like ‘Grow A Garden’ in the future.”

"Charting Our Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Path Forward" Overview

In November, Dietrich College hosted a forum, “Charting Our Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Path Forward.” The forum provided an overview of the implementation of our efforts since the launch of our strategic plan. Additionally, the forum highlighted the many contributions made by our faculty, staff and students. We are grateful for their time, talent and dedication to help build a community that overcomes obstacles and where we all feel (and know) we belong. It also was an opportunity for our community to learn from our Vice Provost and Chief Diversity Officer Dr. Wanda Heading-Grant about university-wide initiatives and her vision for inclusive excellence. While we are happy to be forging forward, Dietrich College will remain steadfast in our commitment to building a diverse, equitable, and inclusive community that endures for years to come. Thank you for doing your part! Only together can we enact greater change and deliver a lasting impact.

In November, Dietrich College hosted a forum, “Charting Our Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Path Forward.” The forum provided an overview of the implementation of our efforts since the launch of our strategic plan. Additionally, the forum highlighted the many contributions made by our faculty, staff and students. We are grateful for their time, talent and dedication to help build a community that overcomes obstacles and where we all feel (and know) we belong. It also was an opportunity for our community to learn from our Vice Provost and Chief Diversity Officer Dr. Wanda Heading-Grant about university-wide initiatives and her vision for inclusive excellence. While we are happy to be forging forward, Dietrich College will remain steadfast in our commitment to building a diverse, equitable, and inclusive community that endures for years to come. Thank you for doing your part! Only together can we enact greater change and deliver a lasting impact.

The forum’s slideshow is available via the link below. You will need to log into Box utilizing your Andrew ID.

We encourage you to provide feedback on the forum and Dietrich College's diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts on the following Google Form.